UNDERGROUND RAILROAD IN VERMONT: A Multi-Colored Bucket List

By Paul Abramson

When we think of Vermont, fall colors, maple syrup and Bernie Sanders come to mind, perhaps some other notable achievements like Ben and Jerry’s ice cream do as well. Here’s something else to add to that list. Put it close to the top. A historic site of the Underground Railroad.

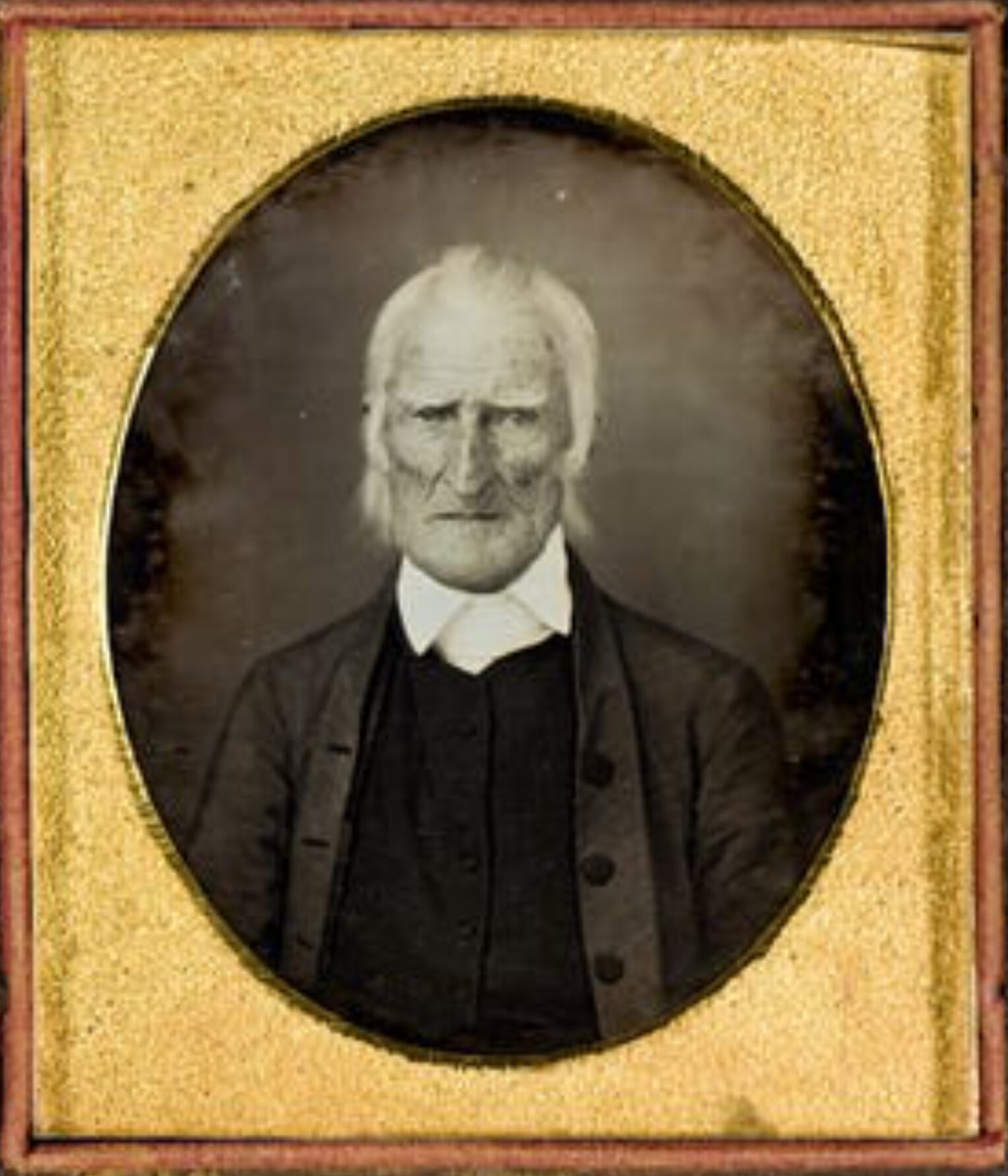

In 1792, the Quaker Thomas Robinson, a rather scary looking guy, certainly as he got older, with sunken cheeks but very prominent cheekbones, a thin scowling mouth and intense beady eyes that looked simultaneously frightened yet skeptical, gathered up his wife and children to collectively say good riddance to Rhode Island, and then hightailed it out to the greener pastures of Vermont, the town of Ferrisburgh, to be exact. For the next 170 years his children, grand-children and great grandchildren lived and prospered on the land that Thomas Robinson originally purchased, until in 1961, when the whole shebang - house, hearth, acreage and artifacts - became a museum, the Rokeby Museum. Throughout the nearly 2 centuries of occupancy, the Robinson’s shared that homestead with friends and extended family members, but also, notably, fugitive slaves. Under the auspices of Rowland Thomas Robinson, the son of Thomas and Jemima Fish, the Rokeby farmstead served as a safe house along the Underground Railroad. Besides devotion to abolitionist causes, future generations of Robinsons had also dabbled in the arts, some becoming quite celebrated authors and illustrators.

The Robinson manor and the outer buildings remain intact, and many of the trails through the cultivated fields and acres do as well, though the latter have now been reclaimed by Mother Nature, in the form of woods. Tania L. Abramson and I, both Editors at BREATHE, recently spent a thoroughly engaging afternoon there, exploring the museum and its historic documents, that had the effect of bringing the fugitive slaves who passed through the Robinson home back to life once again. We then strolled through the trails that braid the property, albeit when the mosquitos seemed especially hungry.

There are obviously many ways to celebrate the lives of Black, Brown and Native Americans. One strategy we have chosen is to visit important historical sites, another prior destination of ours being the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. I can recommend many other sites of historical significance to Black, Brown and Native Americans, but the list is long and easily discoverable through internet searches.

Tania and I like to call our meandering pilgrimage a multi-colored bucket list of the real America, not simply the white-washed version we all learned about in school.

Back to Main Page

The Rokeby Museum

Thomas Robinson